Project Objectives

From 1999 to 2002, the Victims of Crime: A Social Work Response demonstration project worked to fulfill its three objectives:

Objective 1: Conduct a Professional Awareness Campaign

To conduct the professional awareness campaign, the NASW project developed and disseminated articles for professional association newsletters, a special NASW newsletter edition, a crime victims and social work Web site, surveys targeting social work practitioners and schools of social work, and manuscripts for publication in professional journals.

Newsletter Articles

The project was given high visibility in state and national NASW newsletters. An article highlighting victim assistance as an emerging field of practice was published in the February 2000 edition of NASW News, the association’s national newsletter. Additional articles on National Crime Victims’ Rights Week and universal screening in domestic violence were disseminated to all NASW chapters. Articles about the project also appeared in the fall 1999 issue of VISIONS, a publication of the Crime Victim Services Division of the Texas Office of the Attorney General; the Texas District and County Attorneys Association magazine; and the March 2000 issue of Psychotherapy Finances, a newsletter for behavioral health providers.

Special Insert

A special 8-page insert entitled “Responding to the Needs of Crime Victims: An Introductory Guide for Social Workers” was published in the June 2000 issue of NASW/Texas Network. It contained information on the history of the crime victims’ movement, victim compensation, victims’ rights, crisis response to crime victims, Web sites, books, national and state resources, needs of special populations, victim impact statements, safety planning, universal screening for victims, posttraumatic stress disorder, and vicarious trauma for social workers. The well-received guide was distributed at workshops, conferences, state and national NASW leadership meetings, and state child welfare network meetings.

Web Page

A social work and crime victims Web site, developed especially for the project, contained information about the project, newsletter articles, the introductory guide, project advisory committee members, the Texas Crime Victim Assistance Social Work Directory, and links to other victim assistance organizations and resources. The Web site received an average of 200 hits per month and was closed when the project ended.

Surveys

The practitioner survey, used as a training needs assessment, was sent to all licensed social workers in Texas and 1,497 (18 percent) responded. Social work practitioners were asked about their current involvement with crime victim services, the level of training they had received, their continuing education needs, and whether they were currently practicing in the victim assistance field.

|

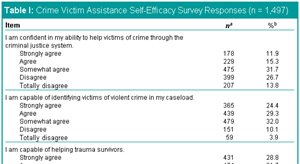

The survey also looked at the personal factors that contribute to crime victim assistance self-efficacy; that is, social workers’ self-appraisal of their capacity to respond to crime victims’ needs. Respondents felt most capable of identifying elder abuse, helping trauma survivors, identifying victims of violent crime in their caseloads, and assisting victims with safety planning (table 1). Respondents felt less capable of assisting with victim impact statements, helping survivors of terrorist actions or multiple shootings, helping survivors through the criminal justice system, and helping fill out crime victim compensation applications.

|

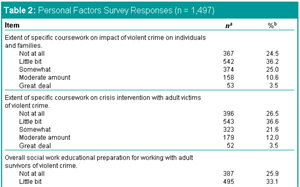

Survey questions about personal factors relating to social workers’ self-efficacy included the amount of personal and professional experience working with victims of crime, academic preparation, and continuing education (table 2). Nearly 82 percent had professional experience working with crime victims, and more than 50 percent said they personally had been affected to some extent by violent crime. Almost 61 percent said they had little to no coursework on the impact of violent crime on individuals and families, and nearly 63 percent said they had a little to no coursework on crisis intervention with adult victims of violent crime. Almost 31 percent had a moderate amount to a great deal of continuing education on working with adult victims of violent crime.

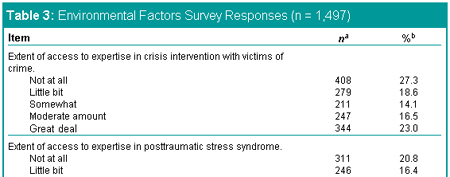

Environmental factors are aspects within a social worker’s practice setting that facilitate his or her self-efficacy (table 3). They include access to expertise, questions on intake forms that screen for particular issues, agency participation in community coordination for victim assistance services, and agency policies on violence and secondary trauma. More than 44 percent said their agency’s intake forms had no specific questions to screen for adult violent victimization, and almost 43 percent said they had no specific intake form questions to screen for violent victimization of children. However, nearly 54 percent of respondents said they had somewhat to a great deal of access to persons with expertise in crisis intervention with adult victims and almost 62 percent in posttraumatic stress disorder, one of the most common mental health risks for crime victims. With the possibility for secondary trauma so critical, it was surprising and dismaying that more than 53 percent of respondents said their agency personnel policies did not address secondary trauma for workers.

|

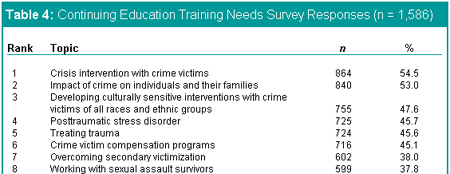

Considering that so many social workers identify with mental health practice, it is not surprising that their top 10 training needs were focused on working directly with crime survivors. Perhaps to make up for the lack of academic training, the number one request was for crisis intervention training with crime victims. Table 4 displays the 15 most often requested topics for additional continuing education training.

|

The social work education survey was sent to all 27 accredited bachelor of social work (BSW) programs and the 6 master of social work (MSW) programs in Texas. The survey yielded information on the extent to which content on victim assistance services had been incorporated into the required curriculum or offered through specialized electives. Additionally, faculty with practice, teaching, and research expertise in the victim assistance area and field placement opportunities for students were identified.

A total of 29 programs—23 BSW and 6 MSW—responded to the survey. They provided information on 52 courses; 11 were MSW level, 35 were BSW level, and 6 were cross-listed for both undergraduate and graduate students. Only 5 of the MSW courses were required, but 27of the BSW courses were required. Victim assistance content seemed to be evenly distributed among required courses in introduction to social work, human behavior and the social environment, social work methods or practice, and policy. Elective courses tended to be in criminology and domestic and family violence.

Required curriculum content courses were more likely to cover the psychological, social, and emotional impact of crime; policy issues such as the Victims of Crime Act and the Violence Against Women Act; crisis intervention; culturally sensitive practice; the impact of race, ethnicity, and gender; and perpetrator dynamics. They were less likely to address victim impact statements, victim restitution programs, victim-offender mediation, identification and screening techniques, death notification, and secondary trauma. Some of these issues may be considered more appropriate for elective courses or on-the-job training through field placements.

All but five of the responding programs indicated they had arranged internships for students in the victim assistance field. These field placements were in local police departments, prosecutors’ offices, sexual assault programs, adult protective services, and local domestic violence agencies. Eight programs offered scholarships to students interested in the victim assistance field. Not all programs had faculty with victim assistance expertise; the16 faculty members identified represented only 11 programs.

Findings from the education survey confirm that although social work faculties are aware of the opportunities for professional development of students in the victim assistance field, they may need additional resources to include more classroom content on crime victims and victim assistance. The limited number of faculty with expertise in this area severely limits the opportunity for its inclusion in the classroom. Providing schools with classroom curriculum materials may be an important step toward remedying this situation.

Articles for Professional Journals

To ensure that the project’s work was a permanent part of the social work literature, the project developed and submitted for publication at least two manuscripts to professional social work journals.8 Additionally, a policy statement on crime victim assistance was published in Social Work Speaks, Seventh Edition,9 NASW’s official publication on social policy positions and statements, which is widely distributed to NASW members and policy classes in professional schools of social work.

Objective 2: Provide Introductory Training to Social Workers on Crime Victims' Rights and Services

The second objective focused on providing continuing education training to social workers in the field and designing materials to educate future social workers in the classroom. The continuing education workshop to educate social workers about the impact of violent crime and crime victims’ rights and services was conceived as a 60- to 90-minute program that could be delivered during local NASW branch meetings.

Workshop Curriculum

The workshop curriculum included information on the prevalence of violent crime, the history of the victim assistance field, federal and state laws that encompass crime victims’ rights, crime victim compensation, victim impact statements, the role of victim assistance advocates, victim reactions to crime, and an overview of intervention issues. Trainer and participant manuals and standardized evaluation forms for both participants and trainers were developed.

The curriculum was pilot tested at the local Denton, Texas, NASW branch, the November 2000 NASW national conference in Baltimore, and state conferences in Alaska, Florida, Missouri, and Texas.The project also received feedback on the curriculum and the project itself at the opening plenary session of the Missouri Victims Assistance Association conference in March 2001.

Trainers

To conduct the workshop, volunteer trainers were recruited through project advisory committee members, the practitioner survey, and Web site and newsletter notices. Preference was given to individuals who were working in the victim assistance field. The goal was to find a social worker with victim assistance experience from each local NASW Texas branch. Although many people were interested in becoming trainers, not all the social workers had the necessary experience. It sometimes was more helpful to send a social worker from another community to conduct the training and discuss sensitive issues. If a trainer was not from a local victim assistance service provider, representatives from local providers were invited to attend the training. Trainers were given a small honorarium for their time.

Train-the-Trainer Sessions

Nearly 100 volunteers attended 5 train-the-trainer sessions conducted by project staff. Each volunteer was given a trainer’s manual, participant manual, evaluation forms, and additional brochures and pamphlets from statewide victim assistance organizations. The participant manual included the workshop agenda, its goal and objectives, and information on victims’ general reactions to crime, crisis intervention issues, services provided by victim assistance programs, victims’ resiliency, violent crime and special populations, crime victims’ rights, and state and national organizations’ Web sites and phone numbers. Pamphlet topics included crime victim compensation, protective orders, sexual assault and domestic violence, and state and local resources.

Trainings were certified for continuing education units and delivered in 70 NASW local branches in 5 states. An overwhelming majority—80 percent—of participants at all training sites felt the workshop information would be helpful in their work. Respondents identified services and resources for crime victims, crime victims’ rights, and crime victim compensation as the top three areas of newly learned information. They also learned about victim impact statements, the emotional impact of crime and victims’ responses, and working with the criminal justice system. Several participants noted that they did not know violent crime included domestic violence. Respondents also mentioned the role of victim advocates and the VINE (Victim Information Notification Everyday) automated hotline service.

Evaluations

A review of more than 300 workshop evaluations showed that as a result of the training, 86 percent of participants now are able to identify rights of crime victims, 83 percent can describe the emotional impact of violent crime on individuals and their families, 75 percent can describe services to crime victims, and 86 percent understand the role of victim impact statements. Additionally, 92 percent said the handouts were useful, and 86 percent said they would recommend the training to other social workers.

Participants said additional training was needed on topics such as clinically oriented skill building, crisis intervention, domestic violence, safety planning, forensic interviewing, working with child victims of crime, and working with victims of clergy abuse.

Volunteer trainers felt their communities benefited from the workshop. When asked how it will help participants assist crime victims, trainer comments included the following:

- “Participants will now be much better prepared to assist crime victims, understand their needs, and have referral information at their fingertips.”

- “Our court system [tribal] currently has no victim statement restorative justice program. This is ground-breaking information I could share as a change agent so victims could be heard.”

Trainers also recommended that the curriculum be shared with a diverse group, including students in social work classes, social service providers, medical personnel in hospital emergency rooms and local health departments, and criminal justice professionals (e.g., law enforcement and juvenile justice workers), and that volunteer training be conducted for advocates in crisis centers, workers in psychiatric hospitals and other mental health facilities, teachers, and those who provide services to people with disabilities and the elderly. Several trainers noted that the trainings would be appropriate for the general public. All trainers said they would be willing to conduct the workshop again.

The only significant problem identified by workshop trainers and participants was the time limitation. Several workshops extended their time by nearly an hour because of the enthusiastic response of the participants and the quality of the discussions. As a result of this consistent feedback, the timeframe for the training was expanded to 2–3 hours (from its original 1–1½ hours), depending on whether the trainer includes a viewing of the videotape New Directions from the Field: Victims’ Rights and Services for the 21st Century.10

Social Work Classroom Discussion Guide

The workshop curriculum focused on enhancing the knowledge and skills of practicing social workers; the discussion guide, which addressed the videotape New Directions from the Field: Victims’ Rights and Services for the 21st Century, was aimed at social work students. This 20-minute video reviews the current state of the victim assistance field, including the rights of crime victims, access to services, and continuing education and training. The discussion guide contains general questions to spark classroom dialog and specific questions for each of the video’s three segments. The discussion guide also has an approximate script of the video so that the instructor can easily find specific scenes on the video.

The guide was developed with the help of focus groups of victim assistance professionals working in the field and social work educators and graduate students with experience in the victim assistance field. It was pilot-tested by a diverse group of social work educators during a curriculum development workshop at a Council on Social Work Education annual program meeting in 2001. The video is considered appropriate for viewing in both undergraduate and graduate foundation social work courses that include policy and direct practice.

The introductory workshop curriculum, the New Directions from the Field videotape and discussion guide, and this OVC bulletin will be packaged as a crime victim assistance curriculum kit and disseminated to all accredited undergraduate and graduate schools of social work through out the Nation.

Objective 3: Develop Links Between Professional Social Work and Victim Assistance Organizations

Organizational Links

Links among NASW and victim assistance organizations were developed on both state and local levels. Through statewide project advisory committees, the NASW chapters made contact with their state attorneys general, crime victim compensation programs, coalitions against domestic violence and sexual assault, state police, Mothers Against Drunk Driving chapters, and departments of criminal justice. These links led to the development of training programs and support for policy and legislative issues and provided access to additional written materials for dissemination at workshops. In states where links already existed, the project asked for social workers in the victim assistance field to work on a mutual project with their professional membership association.

At the local level, links were made by NASW branches with local crime victim service providers. Staff from domestic violence shelters, sexual assault programs, police departments, and prosecutors’ offices participated in the trainings and brought materials on victim services they provided. Workshops that included local victim assistance advocates were more successful than those that did not involve them.

Texas Crime Victim Assistance Social Work Directory

In the practitioner survey discussed earlier, more than 350 social workers in 118 communities said they provided services to crime victims. Contact information for these social workers and information about their areas of expertise were included in the Texas Crime Victim Assistance Social Work Directory. This directory provided local victim assistance programs with referral information for crime victims who need additional counseling. It also encouraged links among social work education and victim assistance programs and organizations. The directory contained information about Texas social work degree programs, including course content on victim assistance, field placement availability, and faculty members with expertise in the field. The directory was made available online at the NASW Texas chapter Web site (it is no longer available), announced in various victim assistance publications, and distributed at the state victim assistance academy training. Although the directory could foster links at the local level, limited resources did not allow the researchers to clarify or validate the information submitted. Additionally, the cost involved in collecting and verifying information precluded the researchers from recommending that the directory be duplicated by the replication sites.

Objective 4: Replicate the Project With Other NASW Chapters

Because the project was deemed successful in Texas, it was important to test whether it could be replicated in other NASW chapters. In the second and third years of the project, requests for proposals were disseminated to all NASW state chapter executive directors and presidents. Three members of the Texas advisory committee served on a replication site selection committee. Applications were ranked according to the ability of the chapter to address the project objectives. Based on the rankings, the New York State and Florida chapters were selected in year 2 and North Carolina and Alaska were selected in year 3. Each chapter was given a replication grant of $7,500 to $10,000 to help implement the project. Both the Florida and New York chapters are large and have well-developed organizational structures and resources. The North Carolina and Alaska chapters are smaller, which enabled the project to be tested in more rural states.

A replication guide was developed and distributed to assist the four chapters in implementing the project. The guide addressed the project’s objectives, including how to identify volunteer trainers, revise training materials for use in different states, increase professional awareness of the victim assistance field, link with state agencies and organizations, and develop recommendations regarding potential state advisory members and projects.

Each replication site adapted the project to its unique needs. In Florida, for example, the workshop was coupled with state-mandated continuing education on domestic violence to maximize attendance. In Alaska, a statewide teleconference was held to reach social workers who practice in rural and remote areas, and several trainings in rural and remote areas were open to the general community. The New York chapter was able to offer the workshop twice for each local NASW branch.

Both New York and Alaska developed special editions of their newsletters based on the Texas special 8-page insert. The New York edition included a quiz that could be counted toward continuing education credit. The newsletter was widely distributed, including at Career Day of the University at Albany, State University of New York. New York and Alaska also developed Web pages about the project that included the content of the special edition newsletter, links to other victim assistance resources, a list of project advisory committee members and trainers, and local training dates and times. State advisory committees were developed in North Carolina and New York. As a result of the project, the New York State chapter planned to offer additional workshops on therapeutic interventions for work with trauma survivors and how to develop safety plans.

Replication kits were sent to all NASW chapters to encourage them to implement the project. The kits included the replication guide, workshop curriculum, and New Directions from the Field videotape and discussion guide.

| Previous | Contents | Next |

| The Victim Assistance Field and the Profession of Social Work |

March 2006

|